Pain in the back – Kissing Spines

March 28, 2019

Equine veterinary hospital Comments Off on Standing tieback surgery for ‘roarers’

22

15

18

One of the most common complaints we see from owners is back pain, specifically kissing spines. This may have been picked up be a visit with the physiotherapist, chiropractor, or there may have been a change in the horse’s behaviour. Back pain, in particular kissing spines, can be very confusing and frustrating for owners and vets alike. Is the pain originating from the spine, the musculature or is it actually a secondary problem caused by hind limb lameness? This article aims to shed some light on this complicated issue and explain some of the recent research and approaches for dealing with this problem.

What is it?

In simple terms, true ‘kissing spines’ (more formally called ‘impingement of the dorsal spinous processes’) is, as the name suggests, narrowing of the space between the top of the spines (dorsal spinous processes of the vertebrae). These will rub together resulting in boney changes and associated pain. Kissing spines is reported as one of the most common causes of back pain, often related to altered spinous process morphology in T13-T18 and with a high prevalence in jumping and dressage horses due to the amount of ventroflexion required (Jeffcott 1980, Jeffcott 1979) However, in a lot of the cases we see, back pain is actually unrelated to the bone below it. This back pain is either directly attributable to the muscles overlying the bone, the epaxial muscles, or secondary to a hind limb lameness causing strain on those same back muscles. We often see primary muscular pain in horses that have poorly developed top line, so either young horses or horses that have recently had a rest. There are also other causes of back pain to consider such as poor saddle fit and horse-rider mismatch.

How do we diagnose it?

Unfortunately, kissing spines is not as easy to diagnose as it may seem. In our initial clinical exam we aim to establish that back pain is present and that it is not secondary to another issue such as lameness, poor saddle fit or riding style. We start with palpation of the back to identify the presence of back pain. This can be very subjective and does depend on the sensitivity of the individual horse. We then examine the horse for any evidence of lameness, which involves walking, trotting and cantering them under multiple conditions, such as in a straight line and on the lunge. We try and have the horse show us what your main complaint is, which sometimes involves tacking the horse up and seeing them ridden. Surprisingly, most horses don’t actually present with bucking when they have a primary back problem, as bucking requires the use of back muscles which are painful and they are avoiding using. Sometimes we may suggest a treatment phenylbutazone (bute) trial with anti-inflammatories (usually using phenylbutazone/bute) to establish how much of the problem is related to pain, and how much is related to behaviour, which typically won’t improve with this treatment.

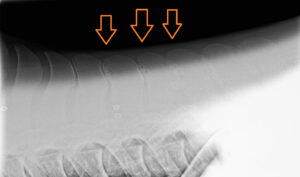

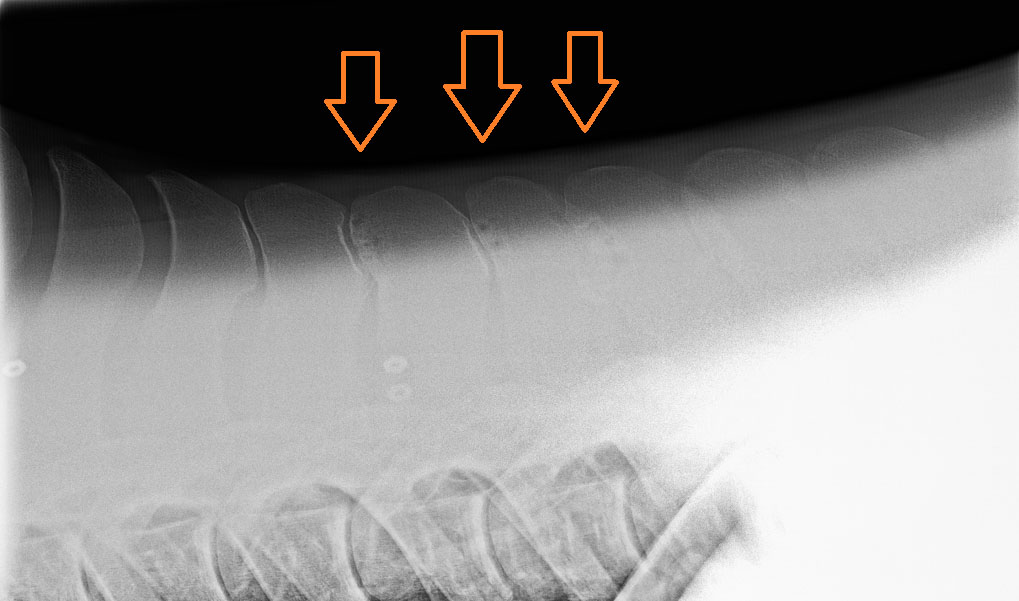

Once we have established that there is clinical primary back pain, radiographs are the gold standard to assess the underlying bone. Interpretation can, however, be complicated. There have been cases of kissing spines reported with minimal boney changes (such as sclerosis and lysis) on radiographs, while other cases have boney changes to the dorsal spinous processes with no clinical problem (Erichsen et. al. 2004). The back is also a mobile structure; with the distance between the dorsal spinous processes strongly affected by the way the horse is standing (Berner et. al. 2012). Depending on how the horse is standing, the space between the dorsal spinous processes can be appear very narrow when they are in fact normal. It is because of this difficulty in interpretation that we often combine radiographs with other modalities to confidently diagnose kissing spines.

Image above: Kissing spine radiography image

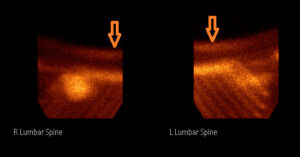

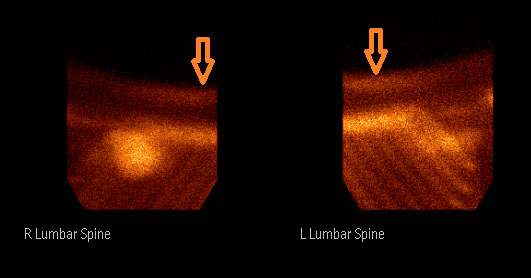

Other modalities you may see your vet use to diagnose kissing spines is infusion of local anaesthetic at the site of the kissing spines identified on radiographs. If this is the primary cause of the problem you should see an improvement of clinical signs. However, infusion of local anesthetic would also show improvement in horses with primary muscular back pain and has even been shown to improve the movement of horses with no clinically identifiable back pain. Your vet may also ultrasound the muscles along the back. Left to right asymmetry of the one the epaxial muscles, the multifidus muscle, has been associated with back pathology (both spinous and muscular). However, this muscle can be difficult to ultrasound and requires experience with the technique. Nuclear scinitgraphy is also an advanced diagnostic modality that is sensitive at picking up active boney changes along the back.

Image above: kissing spine nuclear scinitgraphy image

As you can see, each modality used to identify a primary diagnosis of kissing spines has its advantages and disadvantages. Because of this, we use a combination of different evidence to diagnose kissing spines as the primary back problem:

- Clinical evidence of back pain

- Boney changes of the dorsal spinous processes on radiographs

- Either a positive response to the infusion of local anaesthetic in the region of radiographic changes, asymmetry of the multifius muscle as identified on ultrasound AND/OR increased radiopharmaceutical uptake on nuclear scintigraphy

Treatment goals and options

We have one primary goal in the short and long term treatment of kissing spines and any primary back problem: increase the back musculature. By increasing the musculature along the back, or top line, there is increased support to the underlying boney structures. This is one of the reasons we see back pain as a problem in rested horses who have lost this muscle mass. Our first choice of treatment is an exercise program that builds up the muscular support. These programs usually involving exercises such as lunging in a pessoa, trot poles and transition work. On the ground exercises with carrot stretches are also recommended. Studies are now concluding that the most important of any treatment regime is the exercise program (Turner 2012). However, if the horse is painful and does not engage it’s back and use itself properly, you will not achieve an improvement in the musculature. To provide pain relief in the early stages of the exercise program there are multiple modalities your vet may recommend, some of which include: anti-inflammatories (bute paste), mesotherapy, shockwave and acupuncture along with visits to a physiotherapist. If there is only minimal improvement with an exercise program alone, other treatments include infusion of a corticosteroid at the site of any dorsal process boney changes to reduce the local inflammation. For severe cases that are unresponsive to rehabilitation more invasive methods of treatment include cutting the interspinous ligament between the dorsal spinous processes or partially removing the dorsal spinous process to create more space and stop the impinging.

Image above: Mysotherapy treatment of kissing spine

If you have further questions about kissing spines or back pain, please do not hesitate to contact us or your local vet to discuss what we can do to ensure your horse has a comfortable and long career.

Written by Dr Nicolle Symonds1 and Dr Robin J.W. Bell2

1BSC DVM Resident II Equine Sports Medicine and Rehabilitation

2BVSc MVSc DipECVS Diplomate American College of Equine Sports Medicine and Rehabilitation

Berner D, Winter K, Brehm W, Gerlach K. Influence of head and neck position on radiographic measurement of intervertebral distances between thoracic dorsal spinous processes in clinically sound horses. Equine Veterinary Journal 2012;44:21-26.

Erichsen C, Eksell P, Holm KR et al. Relationship between scintigraphic and radiographic evaluations of spinous processes in the thoracolumbar spine in riding horses without clinical signs of back problems. Equine Veterinary Journal 2004;36:458-465.

Jeffcott LB. Radiographic Features of the Normal Equine Thoracolumbar Spine. Veterinary Radiology 1979;20:140-147.

Jeffcott LB. Disorders of the thoracolumbar spine of the horse–a survey of 443 cases. Equine veterinary journal 1980;12:197-210.

Turner TA. Overriding Spinous Processes (“Kissing Spines”) in Horses: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Outcome in 212 Cases. In: AAEP Proceedings, 2011.

0 Comments